Horror films have a long history with queer themes, fandom, and study. For decades now there have been hundreds of queer horror screenings, convention panels, academic studies, and articles like this fueled by a variety of things ranging from gay themes and creators to a love of camp. Despite this sizable fanbase from the community, horror films for a long time however were not positive to the queer community.

From 1930ish to around even the early 2010s, a lot of the presentation of queer characters is either coded, villains, or a punchline. Even in films celebrated and typically seen as generally positive by queer audiences and academics like Fright Night (Tom Holland/1985), our entry into queerdom within the film are characters who are meant to be perceived by the audience as villains.

Within the mainstream horror of the 1970s and 1980s, there was one popular figure somewhat regularly writing openly queer character in a non-negative light: Dario Argento.

Argento, while problematic at times, wrote several gay or lesbian characters during his golden age. These characters were not coded, villains, or punchlines. There were genuine attempts by Argento to just write those around him into his films. On the use of a lesbian character in 1982’s Tenebrae, Argento stated his goal was to “…recount this subject freely and in an open manner, without interference or being ashamed.” This recounting in Argento’s opinion resulted in the film receiving a harsh adult-only rating in his native Italy, which was highly conservative towards homosexuality.

Tenebrae’s portrayal of lesbianism has been criticized. The Brag’s Michael Louis Kennedy stated “if your entire knowledge of lesbians comes from films like Argento’s Tenebrae, you could be forgiven for thinking that all they do is have showers and get murdered.” But this sort of criticism ignores that the lesbians on display in the film are not like any other lesbians in mainstream horror of that era. They are not titillating like the ones in the Hammer films, they are bitter lovers and Mirella D’Angelo’s Tilde is more developed than most male horror characters at the time.

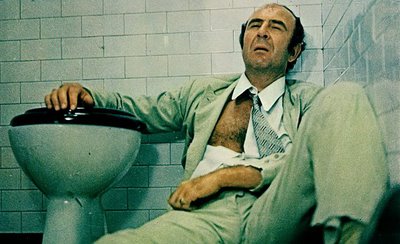

A little over a decade prior, Argento made 1971’s Four Flies on Grey Velvet which features another prominent gay character in Gianni Arrosio, portrayed by revered French actor Jean-Pierre Marielle. Arrosio is a flamboyantly gay detective who is employed by our hero, Roberto, to help uncover his tormentor after Arrosio convinces Roberto to cast his homophobic concerns aside. Like with Tilde, Arrosio is not a predator or villain, is not used exclusively for humour (he is a funny character), and is given a fleshed-out character, admittedly somewhat stereotypically.

It is worth noting, both characters mentioned above are killed: Tilde and her lover are brutally slaughtered while Arrosio is somewhat humiliatingly poisoned (he is given a moment of dignity in knowing he’s solved the case, something he hadn’t done in 3 years). With these deaths and how they go down, it would be very easy to dismiss them as token cannon fodder being used in a similar fashion many characters of colour in horror (eg. The Black Dude Dies First trope) but they really can’t be because of how rare they are.

While not perfect, Four Flies on Grey Velvet’s and Tenebrae’s queer characters are again written as openly gay, both are fully fleshed out, and neither’s sexuality is fetishized or presented as a joke or danger. These are positive portrayals of openly queer characters that arguably not be equaled in horror mainstream cinema until Paranorman (Sam Fell and Chris Butler/2012). Even in Argento’s own filmography, which includes a good number of queer characters outside of these ones, these characters stand apart in terms of their presentation.

And yet, despite how these characters are presented and Argento’s incredibly high reputation among mainstream and art-house horror fans, Argento’s queer presentation is often overlooked when discussing queer horror. General interest publications, Queer outlets, and even horror and genre publications will overlook Argento’s works to favour far more problematic films like May (Lucky McGee/2003), which includes lesbianism through a male gaze and predatory lesbianism, or the incredibly negative A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (Jack Shoulder/1985), which frames queerness itself as a horror when viewed through a queer lens. Only recently did Bloody Disgusting’s Horror Queers podcast see its Joe Lipsett and Trace Thurman discuss how positive and important these portrayals are on their episode on Tenebrae. It’s hard to pinpoint why these works go largely ignored but if one had to guess it might be how blended these characters are into the works.

While noticeable, neither is the lead, the foe, or even a sidekick. These are just people in their films and audiences usually don’t gravitate towards these sorts of side characters. And to be honest that’s a shame because Argento’s celebrity and portrayal of queer characters could be used normalize a marginalized group within mainstream horror. As film analyst Leon Thomas put it in his 2018 video essay The Gay Nightmare: “we shouldn’t have to sieved through subtext to find our gay icons”.

From 1930ish to around even the early 2010s, a lot of the presentation of queer characters is either coded, villains, or a punchline. Even in films celebrated and typically seen as generally positive by queer audiences and academics like Fright Night (Tom Holland/1985), our entry into queerdom within the film are characters who are meant to be perceived by the audience as villains.

Within the mainstream horror of the 1970s and 1980s, there was one popular figure somewhat regularly writing openly queer character in a non-negative light: Dario Argento.

Argento, while problematic at times, wrote several gay or lesbian characters during his golden age. These characters were not coded, villains, or punchlines. There were genuine attempts by Argento to just write those around him into his films. On the use of a lesbian character in 1982’s Tenebrae, Argento stated his goal was to “…recount this subject freely and in an open manner, without interference or being ashamed.” This recounting in Argento’s opinion resulted in the film receiving a harsh adult-only rating in his native Italy, which was highly conservative towards homosexuality.

Tenebrae’s portrayal of lesbianism has been criticized. The Brag’s Michael Louis Kennedy stated “if your entire knowledge of lesbians comes from films like Argento’s Tenebrae, you could be forgiven for thinking that all they do is have showers and get murdered.” But this sort of criticism ignores that the lesbians on display in the film are not like any other lesbians in mainstream horror of that era. They are not titillating like the ones in the Hammer films, they are bitter lovers and Mirella D’Angelo’s Tilde is more developed than most male horror characters at the time.

A little over a decade prior, Argento made 1971’s Four Flies on Grey Velvet which features another prominent gay character in Gianni Arrosio, portrayed by revered French actor Jean-Pierre Marielle. Arrosio is a flamboyantly gay detective who is employed by our hero, Roberto, to help uncover his tormentor after Arrosio convinces Roberto to cast his homophobic concerns aside. Like with Tilde, Arrosio is not a predator or villain, is not used exclusively for humour (he is a funny character), and is given a fleshed-out character, admittedly somewhat stereotypically.

It is worth noting, both characters mentioned above are killed: Tilde and her lover are brutally slaughtered while Arrosio is somewhat humiliatingly poisoned. With these deaths and how they go down, it would be very easy to dismiss them as token cannon fodder being used in a similar fashion many characters of colour in horror (eg. The Black Dude Dies First trope) but they really can’t be because of how rare they are.

While not perfect, Four Flies on Grey Velvet’s and Tenebrae’s queer characters are again written as openly gay, both are fully fleshed out, and neither’s sexuality is fetishized or presented as a joke or danger. These are positive portrayals of openly queer characters that arguably not be equaled in horror mainstream cinema until Paranorman (Sam Fell and Chris Butler/2012). Even in Argento’s own filmography, which includes a good number of queer characters outside of these ones, these characters stand apart in terms of their presentation.

And yet, despite how these characters are presented and Argento’s incredibly high reputation among mainstream and art-house horror fans, Argento’s queer presentation is often overlooked when discussing queer horror. General interest publications, Queer outlets, and even horror and genre publications will overlook Argento’s works to favour far more problematic films like May (Lucky McGee/2003), which includes lesbianism through a male gaze and predatory lesbianism, or the incredibly negative A Nightmare on Elm Street 2: Freddy’s Revenge (Jack Shoulder/1985), which frames queerness itself as a horror when viewed through a queer lens. Only recently did Bloody Disgusting’s Horror Queers podcast see its Joe Lipsett and Trace Thurman discuss how positive and important these portrayals are on their episode on Tenebrae. It’s hard to pinpoint why these works go largely ignored but if one had to guess it might be how blended these characters are into the works.

While noticeable, neither is the lead, the foe, or even a sidekick. These are just people in their films and audiences usually don’t gravitate towards these sorts of side characters. And to be honest that’s a shame because Argento’s celebrity and portrayal of queer characters could be used normalize a marginalized group within mainstream horror. As film analyst Leon Thomas put it in his 2018 video essay The Gay Nightmare: “we shouldn’t have to sieved through subtext to find our gay icons”.

M Rooney is a filmmaker and programmer from Toronto, Canada. He studied fine art at Thompson Rivers University.